Research from the Center for Social Development shows that where voters live can influence their ability to vote.

“In volunteering at the polls, I noticed that equipment malfunctions and other issues seemed relatively common at some sites, explained Gena Gunn McClendon, director of CSD’s Voter Access and Engagement initiative and a co-author of “Will I Be Able to Cast My Ballot?” “I wanted to know whether those conditions are more common at some locations than at others,” McClendon said. The new study offers troubling answers.

The initiative dispatched student researchers to polling locations in St. Louis and St. Louis County on Election Day in 2018. Through arrangements with election authorities in the city and county, the researchers were admitted to polls as election judges. They recorded observations inside and outside of polls.

The findings show that polling conditions vary by the race and income of the communities where polls are located. Polls in communities with higher percentages of Black residents and lower income had fewer election judges, longer lines in the evening, and more interference with the free passage of voters – for example, crowded doorways and electioneering.

The researchers observed voting-machine malfunctions and confusion about polling pads only at predominantly-Black polling sites. Also, high-poverty polling locations were more likely to have conditions – such as lack of seating for voters completing ballots and lack of privacy screens – that prevented voters from completing ballots in privacy, and high-poverty sites were less accessible to people with disabilities.

“Our study offers the first systematic evidence that conditions at the polls operate as a form of voter suppression – suppression by process – even if they were not intentionally designed to suppress voting,” said Michael Sherraden, founding director of CSD and a coauthor of the study.

“Whether suppression by process is intentional misses the point,” Sherraden added. “Systematic bias and neglect are common elements in structural oppression – they are built into common perceptions of how things work, and people overlook them because they are routine.”

“The study highlights yet another form of inequality by place, particularly in the St. Louis context,” said study co-author Kyle Pitzer. “While others have documented these place-based differences on issues like quality of education, health, and social mobility, voting is something else, albeit not unexpected, to bring to the table in discussing the unequal playing field for those living in low-income and segregated neighborhoods. The implications from a neighborhood inequality perspective are dire, in that the differences potentially limit the voices of those experiencing chronic disinvestment and neglect of their neighborhoods – the playing field limits their ability to do something about these conditions via electoral politics.”

The researchers call for improvements in the selection of polling sites and training of poll workers, as well as increases in the number of poll workers and poll pads.

“We see these findings and our preliminary recommendations as opportunities for voters and election authorities to collaborate in the work of strengthening our democracy,” McClendon said. “Ordinary citizens can register new voters, serve as election judges, and work with civic organizations to ensure that Missourians have the identification they need to cast their ballot.”

Aura Aguilar, a CSD research assistant and master’s student in the Brown School, is a co-author of the report.

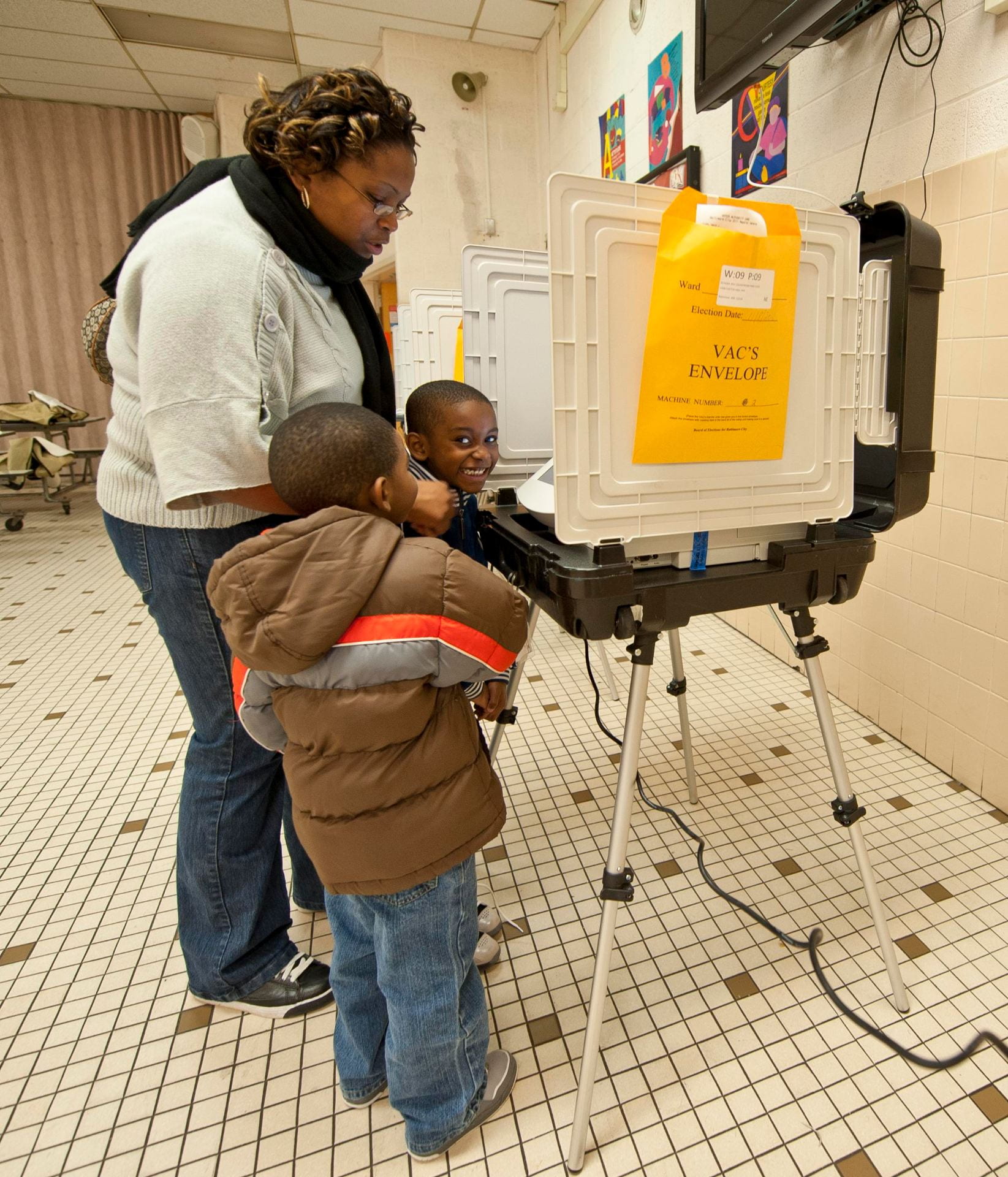

Photo credits

Photo by Eliza Brown on Flickr. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/.

“Teach Your Children,” by GPA Photo Archive on Flickr. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/