Policies to strengthen vulnerable families typically focus either on boosting income for present needs or assets for future priorities. A recent event spotlighted policies to integrate the two approaches for vulnerable families – as we already do for other families.

Economic security remains elusive for many American families. On May 18, U.S. Senator Bob Casey joined researchers, nonprofit leaders, and policy experts to discuss what economic security is and strategies for expanding equitable access to it.

“About 1.5 million U.S. households” live on less than $2 per day, said Trina Shanks, citing research published prior to the pandemic.

“One out of 25 families with children” is included in that number, said Shanks, the Harold R. Johnson Collegiate Professor of Social Work, director of the Center for Equitable Community and Family Well-Being, and a faculty director in the Center for Social Development at Washington University’s Brown School.

Policy sometimes fails to capture the reality of living without economic security, Shanks noted. For some, it’s “living paycheck to paycheck, not being able to make ends meet.” For others, it means “being stressed out trying to manage debt loads and finances,” she said.

Casey, Pennsylvania’s senior U.S. senator, drew a connection to policy. “We’re not investing enough in families raising children,” he said. “Every child in America should have the opportunity for economic security and to earn a living wage when they reach adulthood. This is not possible for so many children.”

“We’re not investing enough in families raising children,” he said. “Every child in America should have the opportunity for economic security and to earn a living wage when they reach adulthood. This is not possible for so many children.”

U.S. Senator Bob Casey

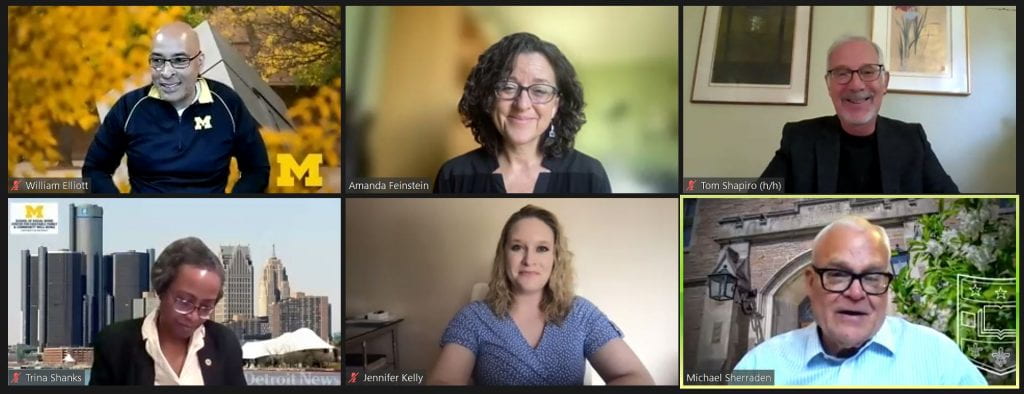

Conceived by William Elliott III, Shanks, and Thomas Shapiro, “What Economic Security Looks Like and How to Get There” focused on strategies for integrating income- and asset-based social policies, and on the possible gains associated with integration.

Elliott is a professor of social work at the University of Michigan, director of the Center on Assets, Education, and Inclusion, and a faculty director in the Center for Social Development at Washington University’s Brown School. Shapiro is the Pokross Professor of Law and Social Policy and former director of the Institute on Assets and Social Policy (now the Institute for Economic and Racial Equity) at Brandeis University.

Elliott offered a conceptualization of the goal: “I think President Roosevelt provided us with a simple but powerful definition of what economic security should look like in America: ‘Liberty requires opportunity to make a living – a living decent according to the standard of the time, a living that gives men not only enough to live by, but something to live for.’”

“I think President Roosevelt provided us with a simple but powerful definition of what economic security should look like in America: ‘Liberty requires opportunity to make a living – a living decent according to the standard of the time, a living that gives men not only enough to live by, but something to live for.’”

William Elliott III

Economic security is about agency, Shapiro said. Income must be “combined with wealth building to provide agency and freedom, so that people have a better chance to transform their own lives in the way that their own ideals and visions and values will take them.”

Social policies, particularly federal ones, focus either on augmenting income or on increasing assets, not on both priorities simultaneously.

“It is sometimes assumed, almost always without empirical evidence, that income-support policies and asset-building policies are in some kind of competition with one another,” said Michael Sherraden, George Warren Brown Distinguished University Professor at Washington University and Founding Director of the Center for Social Development in the university’s Brown School.

“We know from common sense that both sufficient income and sufficient assets are necessary for human stability and social development,” Sherraden noted. “Humans must eat today and also invest for tomorrow.”

Elliott said, “Income provides the foundation from which to catapult families out of poverty. Assets are the inertia that empowers them with the capability to not only move out of poverty, but pursue happiness.”

Leaving poverty and planning for the future can be difficult when income is unpredictable and savings too meager to fill the gap.

“We have a dynamic in the United States where people’s income is consistently moving up and down each month,” said Amy Castro, assistant professor of social policy and practice at the University of Pennsylvania and founding director of the university’s Center for Guaranteed Income Research.

“What’s new is that that income volatility is moving farther up the income ladder,” she continued. “We’re talking about gig workers, adjunct professors, in many cases contingent laborers in the legal field, people who cannot predict their income.” In addition to affecting health, that volatility closes off access to financial products and services, Castro said.

Policies for Today’s Needs, Tomorrow’s Investments

Castro, who studies guaranteed-income interventions, described research on the use of unconditional cash transfers to address income volatility and economic insecurity. Over 150 pilot programs are testing such interventions, she said. The pilots provide a fixed, recurring sum to a select group of people. For example, Castro is studying a pilot program that pays $500 monthly for 24 months to 125 low-income residents of Stockton, California.

Initial findings from the pilot show that the monthly payments reduced income fluctuations, improved recipients’ mental health, and increased their chances of finding full-time employment.

She said she hopes that the work will fill “large gaps in the research around how cash can support individuals and how cash can support families.” By better understanding how the effects of the monthly grants are shaped by grant amounts, payment timing, and the policy environments where payments are made, Castro said, “we can think meaningfully about pairing unconditional cash policies with financial inclusion, financial coaching, and asset building strategies.”

Acknowledging that “Cash infusions – the most basic income supports – can go a long way in reducing poverty, especially for communities of color,” Signe-Mary McKernan noted that the Black–White difference in wealth is actually greater than the difference in income.

“In 2019, the typical White family had eight times the wealth of the typical Black family and five times the wealth of the typical Hispanic family,” said McKernan, who is vice president of labor, human services, and population at the Urban Institute and codirector of the Institute’s Opportunity and Ownership Initiative.

“The origins of this wealth inequity lie in the policies, programs, and institutional practices which created pathways to building wealth for White families while creating barriers to building wealth for Black families,” McKernan said. “Our country’s current focus on racial justice and economic security provides the opportunity to change this trajectory.”

McKernan illustrated the potential of integration by citing policies from Pennsylvania, St. Louis, and the District of Columbia. For example, the nation’s capital provides a credit matching the amount residents receive through the federal earned income tax credit and, through the Strong Families, Strong Future pilot, is testing $900 monthly guaranteed-income payments to low-income mothers. The District also has created Baby Bonds and Individual Development Account programs.

The District, McKernan said, has adopted an integrated approach that targets both “the income and the wealth sides of the balance sheet.”

Casey also discussed specific measures to bolster economic security. “One of the things we can do” he said, “is to help families have a savings account for children.” The senator discussed his Five Freedoms for America’s Children Plan, which includes a proposal for a federal children’s account policy.

“We need a national children’s savings account,” Casey said. “This is something that every child should start their life with,” he continued, adding, “This is something we need to do. This is something the federal government should do. We can’t just point a finger at states and say it’s up to you to provide these opportunities.”

“We need a national children’s savings account… This is something the federal government should do. We can’t just point a finger at states and say it’s up to you to provide these opportunities.”

U.S. Senator Bob Casey

Federal supports for business ownership also offer a path to economic mobility, said Connie Evans, president and CEO of the Association for Enterprise Opportunity. “We’re talking about taking people from poverty and using business ownership and self-employment as a social and economic mobility strategy,” she said.

Evans recommended supports to train would-be entrepreneurs in starting businesses and expand access to funding. Within the last year, the Association for Enterprise Opportunity has given $15 billion in grants to Black business owners, each receiving $10,000. Evans said that over 99% of the recipients are still in business.

“We recognize business ownership as being key to policies that want to combine and support both income and wealth building,” Evans said.

Creating Change

Several panelists noted that moving federal policy involves persuading policymakers to act.

Persuasion, Shapiro emphasized, requires compelling “storytelling that centers the experience, the values, and the voices of people whose lives are being transformed.”

“We need to make much more concrete … what the pilots and demonstrations are showing us,” Shapiro said, stressed the need to develop narratives that “tap very deeply into what should be deeply held American values.”

Bill Zavarello offered a similar perspective: “A holistic approach to antipoverty or to economic empowerment” goes beyond saying, “Here are the policies that we need or should be.” Zavarello, a policy consultant and advocate, served on the staff of the House Financial Services Committee and was a founding staff member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus.

Advocates, he said, must “design a very particular advocacy strategy that unites us as a field and targets the exact people that are in the position to help us accomplish the goal.”

Sherraden concluded the event with a note of optimism. “Until major change happens, it’s impossible to even imagine it,” he said. “Still, at times in the past, people have been able to create new policy directions.”

Noting that Zavarello, Evans, and McKernan stressed the importance of specifying an operable policy design that can be implemented, Sherraden added that sustainability is also imperative.

“It’s not it’s not good enough to just say, ‘Oh, I think we should give this amount of money to this group,’” he said. “We really have to know how that will work, and how it will be put in place. Who will run it? Will it be effective? And will it be sustainable over time? These are practical policy standards that can’t be separated from this discussion.”

“We have, in Child Development Accounts, been working on a practical policy design,” Sherraden continued. “We have put it in place in a number of States. Now it is on a sustainable policy platform. It has bipartisan support.”

Sherraden also emphasized the role of evidence in formulating policy. “We should not underestimate the value of applied research testing innovations,” he said.

“I really believe that evidence can matter,” he added. “It’s always messy. It’s always a hard fight. If we have the evidence, it’s possible to make progress.”

“What Economic Security Looks Like and How to Get There” was sponsored by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, the University of Michigan School of Social Work, the Grand Challenges for Social Work initiative’s Network to Reduce Extreme Economic Inequality, the Center for Social Development, and the Institute for Economic and Racial Equity at Brandeis University.

Remarks by William Elliott III are available in a CSD Perspective, and video of the event may be accessed here.